Comparing Rail and Pipeline Safety

Incidents as a Determining Factor of Safety

There has been a lot of discussion by industry analysts, governments, government agencies and the general public about rail versus pipeline safety for transporting crude oil. On balance, the perception among these groups appears to be that pipelines are safer than rail for moving crude oil.

Incidents

Some of this perception comes from a study by the Fraser Institute citing that pipelines are safer than rail because rail has more incidents with releases than pipelines. Using only the number of incidents to arrive at this conclusion, one would have to assume that all incidents are equal in spill volume and distance travelled which could hardly be true. This flaw in the comparison has led to the unwarranted conclusion that pipelines are safer than using rail.

Incident Rate

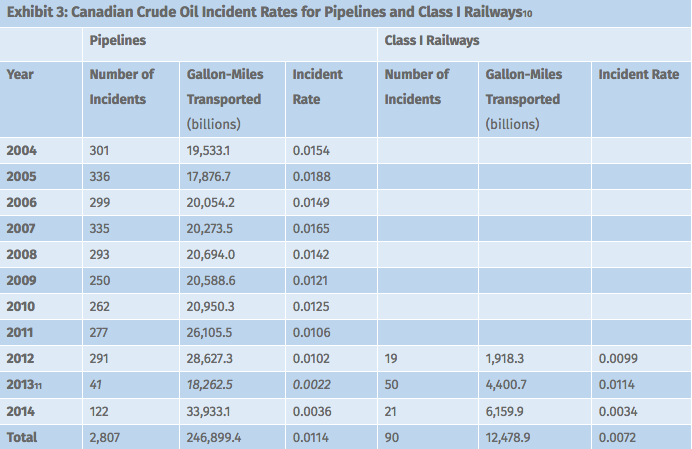

An other study by Oliver Wyman resolves the issue by combining three incident elements into an Incident Rate as shown below:

- The total volume of crude spilled by each mode (annual gallons)

- The total volume each mode transports (annual gallons)

- The total distance the crude oil is moved (annual miles)